October 18, 2017

By Haroon Baloch (Bytes for All Pakistan)

Maria Xynou (OONI)

Arturo Filastò (OONI)

By Haroon Baloch (Bytes for All Pakistan)

Maria Xynou (OONI)

Arturo Filastò (OONI)

Islamabad: Political dissent in Pakistan under threat, government censors online content - PC: Haroon Baloch

A research study by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) and Bytes for All Pakistan.

Table of contents

Country: Pakistan

Probed ISPs: AS132165, AS135661, AS17911, AS23674, AS24499, AS36351, AS38264, AS38547, AS38710, AS45595, AS45669, AS45773, AS45814, AS53889, AS55714, AS56167, AS58895, AS59257, AS9260, AS9387, AS9541, AS9557 (22 ISPs)

OONI tests: Web Connectivity, HTTP Invalid Request Line, HTTP Header Field Manipulation, Vanilla Tor, Facebook Messenger test, WhatsApp test

Testing period: 5th October 2014 to 22nd September 2017 (3 years)

Censorship methods: DNS tampering and HTTP transparent proxies serving blockpages

Key Findings

We confirm detection of 210 blocked URLs in Pakistan. Explicit blockpages were observed for many of these URLs, while others were blocked by means of DNS tampering.

Many of the blocked URLs are considered blasphemous under Pakistan’s Penal Code for hosting content related to the controversial “Draw Mohammed Day” campaign. Geopolitical power dynamics appear to be reinforced through theblocking of sites run by ethnic minority groups.

Pakistani ISPs appear to be applying “smart filters”, selectively blocking access to specific web pages hosted on the unencrypted HTTP version of sites, rather than blocking access to entire domains. Overall, we only found ISPs to be blocking the HTTP version of sites, potentially enabling censorship circumvention over HTTPS (for sites that support encrypted HTTPS connections).

On a positive note, popular communications apps, including WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, were accessible during the testing period. We find that the Tor network, which enables its users to browse the web anonymously, was mostlyaccessible.

Introduction

This study is part of an ongoing effort to examine internet censorship in Pakistan and in more than 200 other countriesaround the world.

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) and Bytes for All Pakistan collaborated on a joint research study to examine internet censorship in Pakistan through the collection and analysis of network measurements. The aim of our study is to document an aspect of internet governance in Pakistan through the analysis of empirical data.

The following sections of this report provide more detailed information about Pakistan’s network landscape and internet penetration levels, its legal environment with respect to freedom of expression, access to information and privacy, as well as cases of censorship and surveillance that have previously been reported in the country. The remainder of the report documents the methodology and key findings of this study.

DISCLAIMER: This is a research report based on facts collected from network measurements. This report is not reflective of either partner’s personal or official opinions.

Background

Pakistan is a country in transition, and has been experiencing political, economic and security instability for more than a decade. Since 9⁄11, the country has become a flashpoint because of the ongoing US war on terror in the region. Pakistan has been an active non-NATO member and an important ally of the global alliance fighting the war on terror since 9⁄11. Due to its alliance against terror groups including Al-Qaeda, the Afghan Taliban and Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, the country has faced massive internal and external security challenges and economic destabilization. Around 123 USD billion in financial losses were reported by the government of Pakistan in its Economic Survey for 2016-17, and 80,000 Pakistanis have lost their lives to the cause.

On political front, Pakistan witnessed a major shift in governance structure in 2010. Pakistan Peoples Party’s, a center-left party, succeeded in the 2008 general elections, and immediately after assuming the power, it vowed revival and restoration of the defunct 1973 constitution in its original shape through a parliamentary process. As a result, a parliamentary committee on constitutional reforms was constituted who completed its deliberations with all political parties and proposed major administrative and governance related amendments in the defunct constitution. These included restoration of fundamental rights, renouncement of executive powers from the president to the elected parliament, granting provincial autonomy, devolution of departments to the provinces, and allocating 33 percent of seats for women, and 14 seats for non-Muslims in the lower and upper houses of the parliaments. These amendments to the constitution were unanimously approved in April 2010 when the parliament passed the 18^th^ Amendment and the country got rid of anomalies introduced by military dictators between 1979 and 2007. In 2013, another constitutional landmark was achieved in the form of first ever successful completion of five-year tenure of any democratically elected civilian government, and smooth transfer of administrative powers to next civilian government.

While Pakistan has seen several political successes in recent years, it still has a strong influence from a powerful military establishment on the country’s law making under the national security narrative. In 2013, the government enacted the Investigation for Fair Trial Act (IFTA), granting overbroad and disproportionate surveillance powers to intelligence agencies. Similarly, the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA), 2016 adopts a set of ‘unreasonable’ restrictions in Section 37 that allow the administration to block, remove/filter and censor online content in the pretext national security, integrity of Islam, morality, relations with friendly nations, contempt of court, etc. Several provisions in the law also provide heightened punishments, which will have chilling effects on online expression. For example, the provisions related to ‘dignity of a natural person’ (defamation or libel) have also been included to crack down on political dissenters.

As per the latest provisional census results, Pakistan is a country of 207.77 million people with 106.4 million males and 101.3 million females. Of these, 36.3% population is housed in urban areas, while remaining 66.63% lived in rural areas. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) has yet to make the final counts public with more demographics details and characteristics of population such as religions, ethnicities, etc. However, according to previous estimates of PBS, Islam is the largest religion of the country. Around 96% of the population comprises on Muslims, 1.6% Hindus, 1.59% Christians, 0.22% Ahmadi, 0.25% Scheduled Castes and 0.07% other religious minorities.

Demographically, Pakistan is a diverse country with Punjabi, Sindhi, Siraiki, Mohajir (migrants from India), Pashtun, Baluchi, Baruhi, Burushaski, Chitrali and Shina being the major ethnic groups.

Network landscape and internet penetration

In spite of that South Asia is the second least connected region in the world, social media managing companies Hootsuite and We Are Social reported in January 2017 that Pakistan in the South Asia is one of the fastest growing markets for the internet. According to their statistics, internet penetration in Pakistan grew by 20% in 2016, with particularly notable growth of social media at 35%. Most web traffic in Pakistan, like other emerging markets, is generated through mobile phones with its annual increase of 13%. There were at least 140.2 million mobile connections, accounting for 72% of population. Of these, 29% of the connections were mobile broadband (3G/4G).

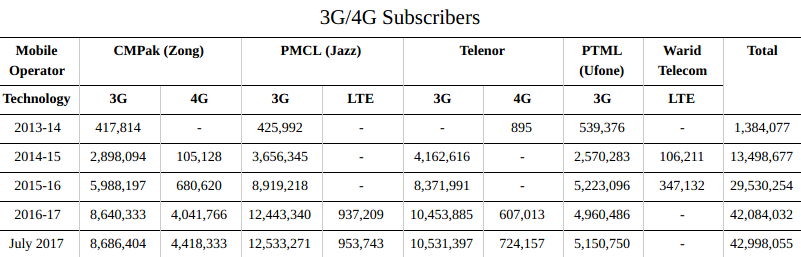

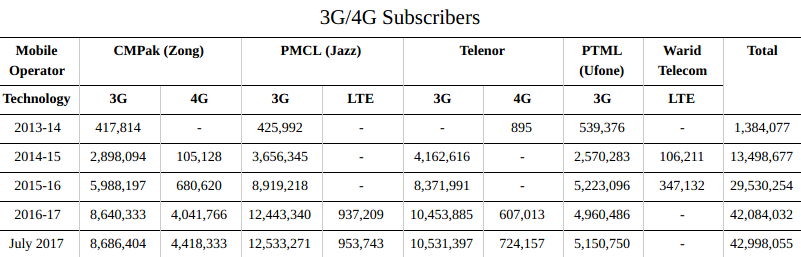

Source: Pakistan Telecommunication Authority - 2017

The total number of internet users in Pakistan in January 2016 was 35.1 million people. According to the report, the 31 million active social media users were most concentrated on Facebook. However, the report also indicated a huge gender divide for social networking; only 22% of females were accessing Facebook in comparison to 78% of males.

The latest figures by the state-owned telecom regulator, Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) claims that internet penetration at the end of July 2017 has reached to 45.5 million users, which accounts to 21.8% in a 207.77 million population. By technology, 94.4% people were mobile broadband subscribers, remaining were connected through DSL, HFC, WiMax, FTTH, EvDO and other technologies. These stats suggest that since the launch of 3G and 4G mobile broadband, these technologies are becoming irrelevant with every passing day. In 2013-14, total number of broadband subscribers were around 3.8 million and most of them relied on EvDO, DSL or WiMax technologies. However, 3G/4G mobile broadband technology was launched in mid-2014, which changed the internet landscape of the country in terms of access expansion. The annual Wireless Local Loop (WLL) subscribers by the end of December 2016 were 375,653, while the Fixed Line Local Loop (FLL) density was 1.46%. By the end of 2016, the annual Fixed Local Line subscribers were 2,692,225. According to PTA figures, annual Cellular Mobile Teledensity in year 2016-17 was 70.85%, whereas accumulated annual Teledensity (Fixed, Wireless Local Loop and Mobile) was 72.41%.

Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited (PTCL) acts as a Pakistan’s internet gateway and bridges the national internet traffic with international traffic through undersea cables, satellite links and terrestrial cables. Pakistan is linked with Middle East, Western Europe and Southeast Asia through SEA-ME-WE-III submarine fiber optic cable system. According to PTA, Pakistan also established SEA-ME-WE-IV for international link improving through IMEWE and SEA-ME-WE-V. Transworld Associates Limited also established first ever private sector undersea fiber optic cable system, TW-1 connecting Pakistan with Oman and UAE. Another undersea fiber optic cable system is currently in the process of completion, called Asia-Africa-Europe (AAE-1). PTCL is also collaborating with a consortium of international telecommunication operators to execute this project.

Additionally, Pakistan is also constructing a terrestrial fiber optic cable network in partnership with China, called the Pakistan-China Optical Fiber Cable (PCOFC) project. This work is being built under China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) initiative and the unstated objective of this cable is to route a significant portion of internet traffic from Pakistan through China, which will put it under the authority of the Rawalpindi Special Communications Organization (SCO). SCO is another government owned telecom operator, which is maintained by Pakistan military with the limited mandate of providing communication services in the disputed Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJK) and Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) regions. During the course of time, SCO has expanded its servicesfrom only landline telephony to Wireless Local Loop (WLL), cellular mobile (GSM), broadband internet (DSL) digital cross connect (DXX), long distance and international (LDI) and domestic private leased networks (DPLN). However, due to its monopoly over business in the region and opposition competition in the sector, private telecom operators were not allowed to operate in these region until 2005 earthquake. Considering people’s plea that telecommunication services expedite rescue efforts during calamities, the government allowed private operators to provide mobile phone services in the regions. Recently, SCO had also made a request to the government to allow expanding its networks to all regions of the country, which was turned down by a parliamentary body.

Per the declared plan, the PCOFC has begun construction at the Khunjarab Pass on the Pakistan-China border and will provide broadband connectivity to Gilgit-Baltistan region. Through this line, Pakistan will connect to Transit Europe-Asia Terrestrial Cable Network and will provide both countries with additional routes for their international internet traffic.

Pakistan has improved in-country fiber optic network connecting almost all cities and several rural areas in recent years, however, still a large population living in the far-flung areas is disconnected. The total length of fiber optic cable network, which is laid with the help of private operators in Pakistan is 22,300 Km. PTCL owns only 5,500 Km while remaining is installed by Wateen, Multinet and Link Direct, all private telecommunication companies.

Pakistan offers a conducive, yet a competitive environment to private telecom investors to operate in the sector, yet the revenue generation from telcos is not as encouraging as it should be. According to State Bank of Pakistan’s figures, share of net foreign direct investment in telecom sector in 2015-16 was 13% with USD 456,371 million revenues. The overall investment in telecom sector in same fiscal year remained \$719.7 million, of which 91.6% was in cellular sector. However, in recent years the government opted the policy to further liberalize telecom sector, and announced auctioning of Next Generation Mobile Services (NGMS) broadband spectrum licenses in 2013.

In the region, Pakistan is among those countries who launched mobile broadband services quite late. It opened up the bidding process for selling out five broadband spectrums in April 2014 under all three internationally harmonized bands (2100 MHz, 1800 MHz and 850 MHz). Only the new entrants in Pakistan telecom market were eligible to place a bid under 850 MHz. The auction results were announced on April 23, 2014. Two blocks of 2x5 MHz and two blocks of 2x10 MHz were sold under 2100 MHz band. One of the foreign companies also secured more advanced block of 2x10 MHz under 1800 MHz band. Another block of 2x10 MHz was sold in April 2016 under 850 MHz band. The government generated around USD 1.5 billion from these auctions. Recently, the government has also announced to hold auctioning of 3G/4G spectrums in AJK and GB regions.

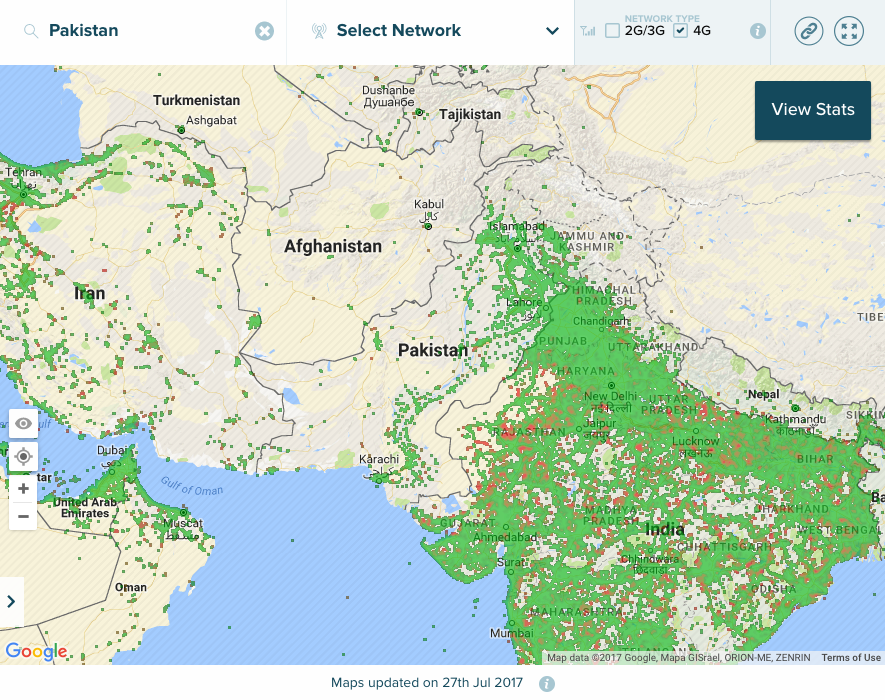

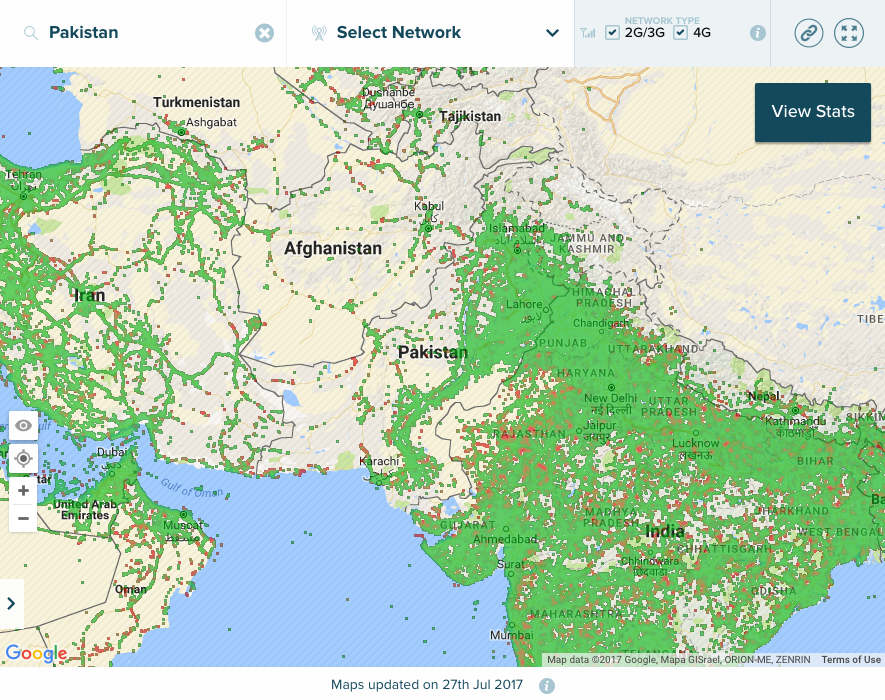

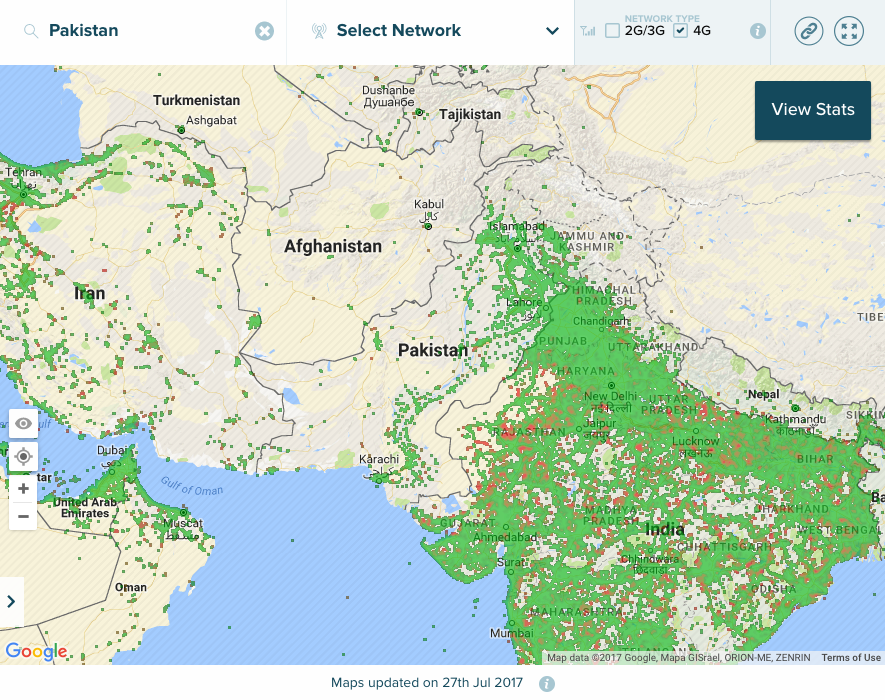

Despite the fact, Pakistan has made some progress after launch of 3G/4G services available to its citizens, however, provision of quality services to citizens is still a huge hurdle in improving access to fast internet. OpenSignal, a private company specializes in wireless coverage mapping through crowdsources data on carrier signal quality from users, suggests in its annual report launched in June 2017 that Pakistan stood among the bottom five countries regarding 4G availability with score of 53.9%. The reason of this is because all mobile operators providing LTE and 4G services are only concentrating in urban area where their economic interests are maximum. (See Coverage Map). In terms of speed, Pakistan is again among bottom 10 countries, however, much better than India, Iran and Sri Lanka in the region. Average 4G speed in Pakistan is 11.71 Mbps in comparison to 5.14 Mbps and 10.24 Mbps in neighboring countries India and Iran respectively.

Source: Pakistan Telecommunication Authority - 2017

The total number of internet users in Pakistan in January 2016 was 35.1 million people. According to the report, the 31 million active social media users were most concentrated on Facebook. However, the report also indicated a huge gender divide for social networking; only 22% of females were accessing Facebook in comparison to 78% of males.

The latest figures by the state-owned telecom regulator, Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) claims that internet penetration at the end of July 2017 has reached to 45.5 million users, which accounts to 21.8% in a 207.77 million population. By technology, 94.4% people were mobile broadband subscribers, remaining were connected through DSL, HFC, WiMax, FTTH, EvDO and other technologies. These stats suggest that since the launch of 3G and 4G mobile broadband, these technologies are becoming irrelevant with every passing day. In 2013-14, total number of broadband subscribers were around 3.8 million and most of them relied on EvDO, DSL or WiMax technologies. However, 3G/4G mobile broadband technology was launched in mid-2014, which changed the internet landscape of the country in terms of access expansion. The annual Wireless Local Loop (WLL) subscribers by the end of December 2016 were 375,653, while the Fixed Line Local Loop (FLL) density was 1.46%. By the end of 2016, the annual Fixed Local Line subscribers were 2,692,225. According to PTA figures, annual Cellular Mobile Teledensity in year 2016-17 was 70.85%, whereas accumulated annual Teledensity (Fixed, Wireless Local Loop and Mobile) was 72.41%.

Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited (PTCL) acts as a Pakistan’s internet gateway and bridges the national internet traffic with international traffic through undersea cables, satellite links and terrestrial cables. Pakistan is linked with Middle East, Western Europe and Southeast Asia through SEA-ME-WE-III submarine fiber optic cable system. According to PTA, Pakistan also established SEA-ME-WE-IV for international link improving through IMEWE and SEA-ME-WE-V. Transworld Associates Limited also established first ever private sector undersea fiber optic cable system, TW-1 connecting Pakistan with Oman and UAE. Another undersea fiber optic cable system is currently in the process of completion, called Asia-Africa-Europe (AAE-1). PTCL is also collaborating with a consortium of international telecommunication operators to execute this project.

Additionally, Pakistan is also constructing a terrestrial fiber optic cable network in partnership with China, called the Pakistan-China Optical Fiber Cable (PCOFC) project. This work is being built under China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) initiative and the unstated objective of this cable is to route a significant portion of internet traffic from Pakistan through China, which will put it under the authority of the Rawalpindi Special Communications Organization (SCO). SCO is another government owned telecom operator, which is maintained by Pakistan military with the limited mandate of providing communication services in the disputed Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJK) and Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) regions. During the course of time, SCO has expanded its servicesfrom only landline telephony to Wireless Local Loop (WLL), cellular mobile (GSM), broadband internet (DSL) digital cross connect (DXX), long distance and international (LDI) and domestic private leased networks (DPLN). However, due to its monopoly over business in the region and opposition competition in the sector, private telecom operators were not allowed to operate in these region until 2005 earthquake. Considering people’s plea that telecommunication services expedite rescue efforts during calamities, the government allowed private operators to provide mobile phone services in the regions. Recently, SCO had also made a request to the government to allow expanding its networks to all regions of the country, which was turned down by a parliamentary body.

Per the declared plan, the PCOFC has begun construction at the Khunjarab Pass on the Pakistan-China border and will provide broadband connectivity to Gilgit-Baltistan region. Through this line, Pakistan will connect to Transit Europe-Asia Terrestrial Cable Network and will provide both countries with additional routes for their international internet traffic.

Pakistan has improved in-country fiber optic network connecting almost all cities and several rural areas in recent years, however, still a large population living in the far-flung areas is disconnected. The total length of fiber optic cable network, which is laid with the help of private operators in Pakistan is 22,300 Km. PTCL owns only 5,500 Km while remaining is installed by Wateen, Multinet and Link Direct, all private telecommunication companies.

Pakistan offers a conducive, yet a competitive environment to private telecom investors to operate in the sector, yet the revenue generation from telcos is not as encouraging as it should be. According to State Bank of Pakistan’s figures, share of net foreign direct investment in telecom sector in 2015-16 was 13% with USD 456,371 million revenues. The overall investment in telecom sector in same fiscal year remained \$719.7 million, of which 91.6% was in cellular sector. However, in recent years the government opted the policy to further liberalize telecom sector, and announced auctioning of Next Generation Mobile Services (NGMS) broadband spectrum licenses in 2013.

In the region, Pakistan is among those countries who launched mobile broadband services quite late. It opened up the bidding process for selling out five broadband spectrums in April 2014 under all three internationally harmonized bands (2100 MHz, 1800 MHz and 850 MHz). Only the new entrants in Pakistan telecom market were eligible to place a bid under 850 MHz. The auction results were announced on April 23, 2014. Two blocks of 2x5 MHz and two blocks of 2x10 MHz were sold under 2100 MHz band. One of the foreign companies also secured more advanced block of 2x10 MHz under 1800 MHz band. Another block of 2x10 MHz was sold in April 2016 under 850 MHz band. The government generated around USD 1.5 billion from these auctions. Recently, the government has also announced to hold auctioning of 3G/4G spectrums in AJK and GB regions.

Despite the fact, Pakistan has made some progress after launch of 3G/4G services available to its citizens, however, provision of quality services to citizens is still a huge hurdle in improving access to fast internet. OpenSignal, a private company specializes in wireless coverage mapping through crowdsources data on carrier signal quality from users, suggests in its annual report launched in June 2017 that Pakistan stood among the bottom five countries regarding 4G availability with score of 53.9%. The reason of this is because all mobile operators providing LTE and 4G services are only concentrating in urban area where their economic interests are maximum. (See Coverage Map). In terms of speed, Pakistan is again among bottom 10 countries, however, much better than India, Iran and Sri Lanka in the region. Average 4G speed in Pakistan is 11.71 Mbps in comparison to 5.14 Mbps and 10.24 Mbps in neighboring countries India and Iran respectively.

Map 1: 4G coverage map of Pakistan (Source: OpenSignal)

Map 1: 4G coverage map of Pakistan (Source: OpenSignal)

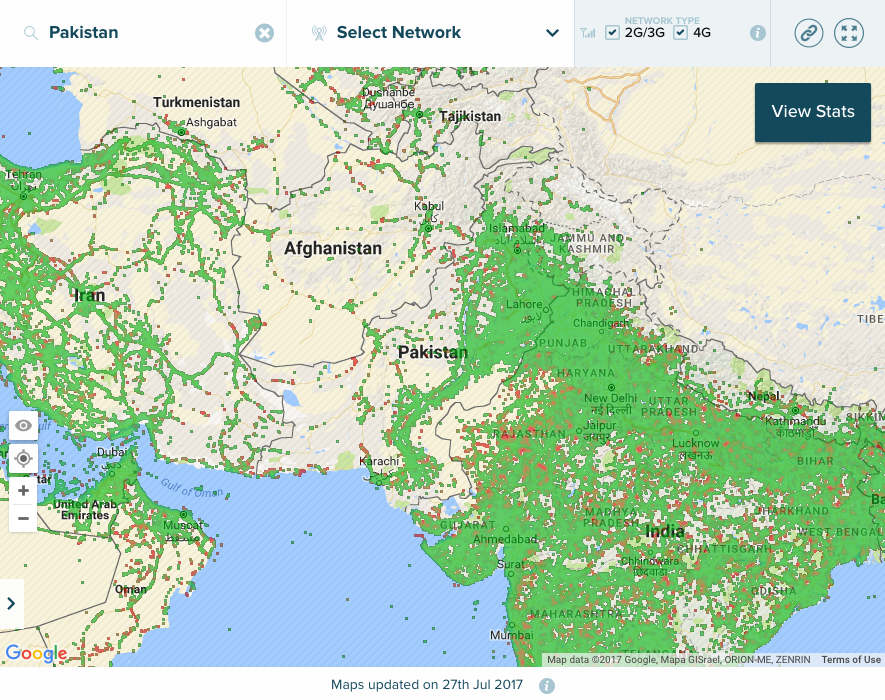

Map 2: 2G/3G/4G coverage map of Pakistan (Source: OpenSignal)

As far as the landscape of Internet Service Providers (ISPs) is concerned, more or less 50 ISPs have been operating in Pakistan. PTCL is one of the three state-owned telecom companies, which is the largest and operating in all 14 regions of the country covering over 2000 urban and rural towns. The other state-owned companies are National Telecommunication Limited (NTC) and SCO. PTCL provides services in broadband, DSL, EvDO, and 3G wireless broadband. Wateen is the second largest ISP of the country which is privately owned and provides DSL and WiMAX wireless broadband services in almost all urban areas across Pakistan. Other leading ISPs include WorldCall Telecom, Wi-Tribe, Qubee, COMSATS Internet Services, Telecard, LinkDotNet, Sharp, NayaTel, DV Com Data, Cyber Internet Services, Super Dialogue, MyTel, MetroTel, Sharp Communications.

At least 17 Long Distance and International (LDI) telephony operators have been operating in the country; three of them are state-owned, whereas FLL operators are 26.

Map 2: 2G/3G/4G coverage map of Pakistan (Source: OpenSignal)

As far as the landscape of Internet Service Providers (ISPs) is concerned, more or less 50 ISPs have been operating in Pakistan. PTCL is one of the three state-owned telecom companies, which is the largest and operating in all 14 regions of the country covering over 2000 urban and rural towns. The other state-owned companies are National Telecommunication Limited (NTC) and SCO. PTCL provides services in broadband, DSL, EvDO, and 3G wireless broadband. Wateen is the second largest ISP of the country which is privately owned and provides DSL and WiMAX wireless broadband services in almost all urban areas across Pakistan. Other leading ISPs include WorldCall Telecom, Wi-Tribe, Qubee, COMSATS Internet Services, Telecard, LinkDotNet, Sharp, NayaTel, DV Com Data, Cyber Internet Services, Super Dialogue, MyTel, MetroTel, Sharp Communications.

At least 17 Long Distance and International (LDI) telephony operators have been operating in the country; three of them are state-owned, whereas FLL operators are 26.

Legal environment

Freedom of expression

The situation regarding freedom of expression, both within offline and online spaces, is becoming increasingly life threatening in Pakistan.

The right to freedom of opinion and expression is guaranteed under Article 19 of the Constitution of Pakistan, which is subject to a set of limitations. These include “restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the glory of Islam or the integrity, security or defense of Pakistan or any part thereof, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, commission of, or incitement to an offense”. A set of subjective and vague terminology in this Article makes it arbitrary and open to interpretation. Also the limitations such as “…glory of Islam or the integrity, security or defense of Pakistan, friendly relations with foreign states, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court” are restrictions that do not meet the criteria provided in the ICCPR.

Regarding online expression, PECA 2016 chalks out comprehensive guidelines for the state to criminalise political and religious dissent. Section 10 focuses on cyber-terrorism, Section 20 pertains to offences against the dignity of a natural person and Section 37 looks into ‘unlawful’ online content. These guidelines sanction unnecessary powers to administrative authorities to stamp down online content and initiate legal action against the accused.

These provisions under PECA suggest heightened punishments of up to 14 years imprisonment and fines up to 50 million rupees or both. Moreover, stifling online expression through criminal courts proceedings in defamation cases is a harsh response. Article 20 of PECA in offences of defamation in online spaces suggests up to three years imprisonment or up to 10 million rupees fine, or both.

PECA contains several terms that are vague and can be misinterpreted and used unlawfully against anyone It does not contain any procedural safeguards (prior to censorship as well as in appeal) against surveillance activities carried out by intelligence agencies, nor does it contain the grounds on which an authority has to consider making use of its powers.

The government also uses the Anti-Terrorism Act, 1997 to criminalise online speech. There are documented cases where the state tried the accused under section 11-W of the Anti-Terrorism Act for sharing ‘objectionable’ material on Facebook. Anti-terrorism courts meted out a thirteen year imprisonment sentence to Rizwan Haider and Saqlain Haider, both belonging to Shia sect, for sharing ‘objectionable’ posts.

Since the start of 2017, Pakistan has been witnessing a planned crackdown against social media activists, political workers and bloggers. The high handedness on human rights movement has manifested a rampant culture of impunity. Abduction of four bloggers namely Waqas Goraya, Asim Saeed, Ahmed Raza Naseer and Salman Haider are a few examples of this. After their release, these bloggers adversely suffered an online smear campaign that associated them with controversial and religiously sensitive content on social media pages.

Cases of forced disappearances are not reported, and those missing have not returned. Pakistan’s record in providing safety to activists, journalists, and civil society members who have been critical of the policies and growing religious radicalization is far from encouraging. A large number of such individuals have been routinely censored, intimidated, been under constant surveillance and attacked in the past. This has inevitably contributed to the narrowing of spaces for peaceful expression, debate, protest, and the exercise of civil liberties.

More recently, the government ordered the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) to take action against social media activists who were criticising military. Subsequently, FIA prepared a list of 200 social media users, summoned them, and confiscated their devices for forensic analyses. This crackdown corroborates the fears that the PECA 2016 is being used to silence political dissent.

Press freedom

Press freedom is guaranteed under Article 19 of the Constitution, which is subject to a set of limitation which do not correspond to the guidelines provided under ICCPR. (See section Freedom of Expression). Print and electronic media in Pakistan are being regularized by state-owned regulators Press Council of Pakistan (PCP) and Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) established under PCP Ordinance 2002 and PEMRA Ordinance 2002. In August 2015, PEMRA formulated a media code of conduct, which is enforced on privately owned electronic media across the country. However, most observers noted that media professionalism and ethics would be more robust if it originated from self-regulatory codes by an independent media itself.

In reality, media regulators such as PEMRA and PCP are functioning as non-autonomous subordinates of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. The government has not ensured that the mandates of media regulators remain autonomous.

In PECA 2016, sections 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 have been introduced, which are potential threat to investigative form of journalism as they not only restrict access to critical but public interest information or intelligence in digital forms, but also criminalize such form of access. However, the government has recently passed the Public Interest Disclosure Bill(whistleblowers protection law) in the National Assembly, which will become law after its passage from the Senate.

Access to information

As a result of 18th amendment, Article 19-A was included in the Constitution guaranteeing the right to information in all matters of public importance subject to regulations and ‘reasonable restrictions’ imposed by the law. However, guidelines for these ‘reasonable restrictions’ are missing in the Constitution leaving space for legislative bodies to introduce interpretations and limitations of their own choice to restrict this right.

Since the passage of 18th amendment, the federal government has not made progress on finalizing legislation on the Right to Information Act (RTI). Observers note this Act, if passed, is possibly the best tool to ensure better accountability in government institutions. However, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab governments have already enacted two impressive laws in their respective provinces. Like the federal government, Baluchistan province has yet to replace its outdated RTI laws with the new ones. Sindh assembly has also passed a new bill called Sindh Transparency and Right to Information Bill 2016, which is still pending for approval from the governor of the province.

Privacy and digital surveillance

Under global human rights law, any interference with the right to privacy can only be justified if it is in accordance with the law, has a legitimate objective and is conducted in a manner that is necessary and proportionate. Rapid advances in technology have posed significant challenges to the right to privacy, yet governments are required to protect and promote this right in the digital age.

Article 14, Clause 1 of the Constitution of Pakistan provides for the inviolability of the privacy of the home, subject to law. However, the Constitution does not expressly protect privacy of communications, digital or otherwise. Moreover, Article 14 does not provide any limitations for laws that restrict the right to privacy to ensure that they are not arbitrary and comply with the principles of necessity and proportionality.

PECA 2016 also legitimizes the state’s activities to snoop into digital communications of the citizens, retain personal data for up to one-year and share it with foreign governments and agencies. PECA 2016 poses a serious threat to the right to privacy as it permits the PTA and the designated investigation agency to access traffic data of telecommunication subscribers and confiscate data and devices without prior warrants from the court under Section 31. Moreover, Section 35 permits decryption of information, making it impossible for persons to be anonymous.

Phone calls are routinely tapped, which was admitted by the state intelligence agencies before the Supreme Court in 2015, when they stated that they were monitoring over 7,000 phone lines every month. In addition, the government has implemented a mass digital surveillance programme under the guise of securing Islamabad. Over 1,800 high-powered cameras have been installed all over Islamabad. These high-definition cameras are technologically advanced and their facial recognition feature links to National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA). Punjab, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwaand Sindh governments have also unveiled their plans to install CCTV cameras in their respective jurisdictions.

Censorship

PTA continues to block over 80,000 websites on grounds of morality and obscenity. Another 200,000 links containing ‘objectionable’ content remains inaccessible in Pakistani cyberspace. In January 2016, PTA on the directions of the Supreme Court also instructed the internet service providers (ISPs) to block 400,000 ‘objectionable’ websites at domain level. However, ISPs reported back that blocking at such a mass scale would be costly.

However, all the websites marked to be blocked were not containing the above-mentioned content. Pakistani government also frequently requests Facebook, Twitter and Google to restrict or remove what they deem to be ‘objectionable content’ in Pakistan.

According to the Facebook transparency report, for the first six months of 2016, it received 719 requests from Pakistani authorities requiring data related to criminal cases, as well as information on 1,029 user accounts. PTA also made 280 requests to Facebook to retain information, while 363 user account data was requested to be preserved for official criminal investigations for 90 days. Facebook also received 25 requests to restrict objectionable and allegedly blasphemous content under the local laws. Between January to June 2014, Facebook restricted 1,773 pieces of content in Pakistan under local blasphemy laws and prohibition of criticism on the state. Pakistan also made a total of 9 removal requests from Twitter between January and June 2016.

On March 27, 2017, the Interior Ministry informed the Islamabad High Court while hearing a case related to online blasphemous content that Facebook removed 85% of ‘objectionable’ material requested by the government of Pakistan.

YouTube remained blocked in Pakistan between September 2012 and January 2016 due to release of a movie trailer, ‘Innocence of Muslims’. However, Ministry of Information Technology and Telecommunication (MoIT&T) claimed that YouTube agreed with the government of Pakistan to entertain content blocking and removal requests from Pakistan cyberspace. Google has since launched a country specific version of YouTube. The new homepage contains content that is curated specifically for Pakistani users that they would see by default when they access YouTube from within Pakistan.

Reported cases of internet censorship and surveillance

Censorship in Pakistan has been one of the biggest stumbling blocks in the way of ensuring swift, open and uninterrupted access to the Internet. Multiple factors have been restricting the access and associated rights, including enabling right of the freedom of expression in online spaces.

Censorship of erotic expression

Since enactment of PECA in 2016, the government has become more empowered to block online expression, and remove/filter digital content under the broad and subjective provisions related to “objectionable content”. In recent months, dozens of cases of blocking and censoring content have been reported on account of obscenity, blasphemy, piecing criticism or political dissent against the government and military policies, matters related to national security, etc. In the pretext of blasphemy, Pakistan placed a blanket ban on Youtube in September 2012, which was restored after three and a half years after reaching an agreement between the government of Pakistan and Google that the latter will entertain future requests to block objectionable content.

In March 2016, PTA submitted a report in the Supreme Court stating that access to at least 84,000 websites and pages have been restricted in Pakistan on account of salacious content. The report further informed the court that another list containing 400,000 links was also handed over to ISPs for blocking at domain level. PTCL informed that it had blocked 200,000 links. However, PTA also expressed its inability to complete this task because it was an expensive exercise for ISPs.

‘Deviant Art’ is another online networking space for ‘artists and art enthusiasts’ aimed to promote liberation of creative expression. The platform is actively being used by Pakistani artists and graphic designers to publish their artistic expression. Bytes for All intermittently receives complaints from Deviant Art’s Pakistani subscribers regarding its inaccessibility inside Pakistan. In March 2014, it was first reported by Anime Artists of Pakistan that the website was blocked in Pakistan. However, it remained accessible until recently when Bytes for All received another complaint from a Karachi based user. After several weeks of being blocked, it is now accessible again in Pakistan.

Censorship of political dissent

The more concerning is the fact, the government has arbitrarily been blocking websites and blogs who would express political dissent online.

‘Khabaristan Times’ was an online portal until January 25, 2017, who produced regular blogs on major national developments in satirical style. Sources privy to PTA confirmed to Bytes for All that they blocked the website for unspecified objectionable content. Admins of Khabaristan Times’s Facebook page on January 30 updated its readers that their website was blocked by the authorities without serving any notice and giving chance to respond to the allegations.

‘The Baloch Hal’ is another example of crushing political dissent of an ethnicity in Pakistan by the State. PTA blocked the website in 2010 and the ban still continues. This portal was the first online English language newspaper of Baluchistan province, which was founded in November 2009. Because of its liberal point of view and touching upon the sensitive conflict related issues in Baluchistan, PTA put it offline. Subsequently, the editor-in-chief of the Baloch Hal, Malik Siraj Akbar allegedly received life threats from the government and intelligence agencies, forcing him to live in exile in the United States.

In April 2015, PTA also blocked a political forum Siasat.PK, which has a known anti-government stance. Siasat.pk is a famous platform where people express their criticism against the government. The case was reported in Pakistani media and after receiving public pressure, the government restored the forum.

Currently, there has been an ongoing crackdown against politico-religious dissent expressed on social media, which enjoys the patronage of the State. A mass censorship campaign is being pushed through a multi-actor approach where the ministry of interior, ministry of information technology and telecommunication, federal investigation agency, PTA and Islamabad High Court (IHC) are on the driving seat.

The State has taken a strict stance against online blasphemy and criticism on Pakistan military. A petition against online blasphemy and alleged involvement of four bloggers for expressing hate against Islam and military was registered in IHC. The court ordered the concerned departments to take stringent measures for protecting the sanctity of Islam and prophet Muhammad (PBUH). PTA, PEMRA and PCP ran a coordinated media campaign warning public to limit their expression according to Article 19, whereby any expression against “integrity of Islam” and “national security” is unlawful. PTA also sent text messages (SMS) to mobile users urging them to complain against those involved in production and circulation of blasphemy or anti-military content online. PTA also wrote to the Facebook and Twitter to remove accounts and anti-Islam content from their platforms. Consequently, the Facebook and Twitter pages Mochi, Bhensa and Roshni were blocked which were managed by four bloggers who went missing in January 2017.

Censorship of religious expression

The pretext of “objectionable content” in Pakistan is overbroad and subjective. Like opposition to political dissent, religious expression of faith-based minorities is censored. Ahmadiyya, Qadiani or Lahori Group is the most persecuted community of the country, who were declared non-Muslim through 2nd Amendment in the Constitution of Pakistan in 1974. Since then, Ahmadiyya have been pushed toward the periphery of the society. The Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) criminalizes their religious expression in public. Similar to physical spaces, their religious expression in online spaces in Pakistan is also banned. In July 2012, PTA blocked Ahmadiyya website, ‘Al-Islam”, which is still inaccessible. Similarly, their other websites including official website of ‘Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha’at-e-Islam Lahore’ and ‘The Persecution of Ahmadiyya Community’ are also blocked.

Use of intrusive FinFisher and HackingTeam solutions

The government has been using intrusive technology such as FinFisher that surveils private communications. FinFisher offers different intrusive modules that silently sit in the recipient’s digital devices and enable remote surveillance such as keylogging, webcam/microphone access, and password collection. In addition, Pakistan contacted HackingTeam to acquire a similar type of intrusion malware suites.

Punjab government’s initiative binds all hotels in Lahore to share guests’ data including foreigners with the city police. Hotel Eye software is introduced which is attached with crime database in their control room. Pakistan lacks in legislative framework that would protect data of citizens.

In the absence of safeguards, such as judicial oversight, state institutions have been carrying out surveillance on digital communications of individuals, groups and organisations. There is increasing concern that local law enforcement agencies (LEAs) and intelligence agencies have the ability to access into a range of devices to capture data, encrypted or otherwise. Following guidelines set out by the government, courts and ministry of information technology, PTA and multiple law enforcement agencies are able to conduct online surveillance and lawfully intercept and monitor data.

The state appears to be using the 2002 Electronic Transaction Ordinance, the Investigation for Fair Trial Act 2013 and the Pakistan Telecommunications (Re-organization) Act 1996 to collect privileged communication and conduct broad surveillance.

Methodology: Measuring internet censorship in Pakistan

The methodology of this study includes the following:

-

Review of the Citizen Lab’s test list for Pakistan

-

OONI network measurement tests

-

Data analysis

A list of URLs that are relevant and commonly accessed in Pakistan was created by the Citizen Lab in 2014 for the purpose of enabling network measurement researchers to examine their accessibility in Pakistan. As part of this study, this list of URLs was reviewed to include additional URLs which - along with other URLs that are commonly accessed around the world - were tested for blocking based on OONI’s free software tests. Such tests were run from local vantage points in Pakistan, and they also examined whether systems that are responsible for censorship, surveillance and traffic manipulation were present in the tested network. Once network measurement data was collected from these tests, the data was subsequently processed and analyzed based on a standardized set of heuristics for detecting internet censorship and traffic manipulation.

The testing period for this study started on 5th October 2014 and concluded on 22nd September 2017.

Review of the Citizen Lab’s test list for Pakistan

OONI network measurement tests

Data analysis

Review of the Citizen Lab’s test list for Pakistan

An important part of identifying censorship is determining which websites to test for blocking.

OONI’s software (called ooniprobe) is designed to examine URLs contained in specific lists (“test lists”) for censorship. By default, ooniprobe examines the “global test list”, which includes a wide range of internationally relevant websites, most of which are in English. These websites fall under 30 categories, which help ensure that a wide range of different types of sites are tested.

In addition to testing the URLs included in the global test list, ooniprobe is also designed to examine a test list which is specifically created for the country that the user is running ooniprobe from, if such a list exists. Unlike the global test list, country-specific test lists include websites that are relevant and commonly accessed within specific countries, often in local languages. Similarly to the global test list, country-specific test lists include websites that fall under the same set of 30 categories.

All test lists are managed by the Citizen Lab on GitHub. As part of this study, the Citizen Lab’s test list for Pakistan was reviewed and more URLs were added to be tested for censorship. Overall, 950 URLs that are relevant to Pakistan were tested. The URLs included in the Citizen Lab’s global list (including 1,107 different URLs) were also tested.

It is important to acknowledge that the findings of this study are only limited to the websites that were tested, and do not necessarily provide a complete view of other censorship events that may have occurred during the testing period.

OONI network measurement tests

As part of this study, the following OONI software tests were run:

-

-

-

-

-

-

The Web Connectivity test was run with the aim of examining whether a set of URLs (included in both the “global test list” and the recently updated “Pakistani test list”) were blocked during the testing period and if so, how. The Vanilla Tor test was run to examine the reachability of the Tor network, while the WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger tests were run to examine whether these instant messaging apps were blocked in Iran during the testing period. The remaining tests were run with the aim of examining whether “middleboxes” (systems placed in the network between the user and a control server) that could potentially be responsible for censorship and/or surveillance were present in the tested networks.

The sections below document how each of these tests are designed.

Web Connectivity

This test examines whether websites are reachable and if they are not, it attempts to determine whether access to them is blocked through DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking or by a transparent HTTP proxy. Specifically, this test is designed to perform the following:

-

Resolver identification

-

DNS lookup

-

TCP connect

-

HTTP GET request

By default, this test performs the above (excluding the first step, which is performed only over the network of the user) both over a control server and over the network of the user. If the results from both networks match, then there is no clear sign of network interference; but if the results are different, the websites that the user is testing are likely censored.

Further information is provided below, explaining how each step performed under the web connectivity test works.

1. Resolver identification

The domain name system (DNS) is what is responsible for transforming a host name (e.g. torproject.org) into an IP address (e.g. 38.229.72.16). Internet Service Providers (ISPs), amongst others, run DNS resolvers which map IP addresses to hostnames. In some circumstances though, ISPs map the requested host names to the wrong IP addresses, which is a form of tampering.

As a first step, the web connectivity test attempts to identify which DNS resolver is being used by the user. It does so by performing a DNS query to special domains (such as whoami.akamai.com) which will disclose the IP address of the resolver.

2. DNS lookup

Once the web connectivity test has identified the DNS resolver of the user, it then attempts to identify which addresses are mapped to the tested host names by the resolver. It does so by performing a DNS lookup, which asks the resolver to disclose which IP addresses are mapped to the tested host names, as well as which other host names are linked to the tested host names under DNS queries.

3. TCP connect

The web connectivity test will then try to connect to the tested websites by attempting to establish a TCP session on port 80 (or port 443 for URLs that begin with HTTPS) for the list of IP addresses that were identified in the previous step (DNS lookup).

4. HTTP GET request

As the web connectivity test connects to tested websites (through the previous step), it sends requests through the HTTP protocol to the servers which are hosting those websites. A server normally responds to an HTTP GET request with the content of the webpage that is requested.

Comparison of results: Identifying censorship

Once the above steps of the web connectivity test are performed both over a control server and over the network of the user, the collected results are then compared with the aim of identifying whether and how tested websites are tampered with. If the compared results do not match, then there is a sign of network interference.

Below are the conditions under which the following types of blocking are identified:

-

DNS blocking: If the DNS responses (such as the IP addresses mapped to host names) do not match.

-

TCP/IP blocking: If a TCP session to connect to websites was not established over the network of the user.

-

HTTP blocking: If the HTTP request over the user’s network failed, or the HTTP status codes don’t match, or all of the following apply:

-

The body length of compared websites (over the control server and the network of the user) differs by some percentage

-

The HTTP headers names do not match

-

The HTML title tags do not match

It’s important to note, however, that DNS resolvers, such as Google or a local ISP, often provide users with IP addresses that are closest to them geographically. Often this is not done with the intent of network tampering, but merely for the purpose of providing users with localized content or faster access to websites. As a result, some false positives might arise in OONI measurements. Other false positives might occur when tested websites serve different content depending on the country that the user is connecting from, or in the cases when websites return failures even though they are not tampered with.

Resolver identification

DNS lookup

TCP connect

HTTP GET request

DNS blocking: If the DNS responses (such as the IP addresses mapped to host names) do not match.

TCP/IP blocking: If a TCP session to connect to websites was not established over the network of the user.

HTTP blocking: If the HTTP request over the user’s network failed, or the HTTP status codes don’t match, or all of the following apply:

- The body length of compared websites (over the control server and the network of the user) differs by some percentage

- The HTTP headers names do not match

- The HTML title tags do not match

HTTP Invalid Request Line test

This test tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”) which could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

Instead of sending a normal HTTP request, this test sends an invalid HTTP request line - containing an invalid HTTP version number, an invalid field count and a huge request method – to an echo service listening on the standard HTTP port. An echo service is a very useful debugging and measurement tool, which simply sends back to the originating source any data it receives. If a middle box is not present in the network between the user and an echo service, then the echo service will send the invalid HTTP request line back to the user, exactly as it received it. In such cases, there is no visible traffic manipulation in the tested network.

If, however, a middle box is present in the tested network, the invalid HTTP request line will be intercepted by the middle box and this may trigger an error and that will subsequently be sent back to OONI’s server. Such errors indicate that software for traffic manipulation is likely placed in the tested network, though it’s not always clear what that software is. In some cases though, censorship and/or surveillance vendors can be identified through the error messages in the received HTTP response. Based on this technique, OONI has previously detected the use of BlueCoat, Squid and Privoxy proxy technologies in networks across multiple countries around the world.

It’s important though to note that a false negative could potentially occur in the hypothetical instance that ISPs are using highly sophisticated censorship and/or surveillance software that is specifically designed to not trigger errors when receiving invalid HTTP request lines like the ones of this test. Furthermore, the presence of a middle box is not necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as they are often used in networks for caching purposes.

HTTP Header Field Manipulation test

This test also tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”) which could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

HTTP is a protocol which transfers or exchanges data across the internet. It does so by handling a client’s request to connect to a server, and a server’s response to a client’s request. Every time a user connects to a server, the user (client) sends a request through the HTTP protocol to that server. Such requests include “HTTP headers”, which transmit various types of information, including the user’s device operating system and the type of browser that is being used. If Firefox is used on Windows, for example, the “user agent header” in the HTTP request will tell the server that a Firefox browser is being used on a Windows operating system.

This test emulates an HTTP request towards a server, but sends HTTP headers that have variations in capitalization. In other words, this test sends HTTP requests which include valid, but non-canonical HTTP headers. Such requests are sent to a backend control server which sends back any data it receives. If OONI receives the HTTP headers exactly as they were sent, then there is no visible presence of a “middle box” in the network that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance and/or traffic manipulation. If, however, such software is present in the tested network, it will likely normalize the invalid headers that are sent or add extra headers.

Depending on whether the HTTP headers that are sent and received from a backend control server are the same or not, OONI is able to evaluate whether software – which could be responsible for traffic manipulation – is present in the tested network.

False negatives, however, could potentially occur in the hypothetical instance that ISPs are using highly sophisticated software that is specifically designed to not interfere with HTTP headers when it receives them. Furthermore, the presence of a middle box is not necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as they are often used in networks for caching purposes.

Vanilla Tor test

This test examines the reachability of the Tor network, which is designed for online anonymity and censorship circumvention.

The Vanilla Tor test attempts to start a connection to the Tor network. If the test successfully bootstraps a connection within a predefined amount of seconds (300 by default), then Tor is considered to be reachable from the vantage point of the user. But if the test does not manage to establish a connection, then the Tor network is likely blocked within the tested network.

WhatsApp test

This test is designed to examine the reachability of both WhatsApp’s app and the WhatsApp web version within a network.

OONI’s WhatsApp test attempts to perform an HTTP GET request, TCP connection and DNS lookup to WhatsApp’s endpoints, registration service and web version over the vantage point of the user. Based on this methodology, WhatsApp’s app is likely blocked if any of the following apply:

-

TCP connections to WhatsApp’s endpoints fail;

-

TCP connections to WhatsApp’s registration service fail;

-

DNS lookups resolve to IP addresses that are not allocated to WhatsApp;

-

HTTP requests to WhatsApp’s registration service do not send back a response to OONI’s servers.

WhatsApp’s web interface (web.whatsapp.com) is likely if any of the following apply:

-

TCP connections to web.whatsapp.com fail;

-

DNS lookups illustrate that a different IP address has been allocated to web.whatsapp.com;

-

HTTP requests to web.whatsapp.com do not send back a consistent response to OONI’s servers.

TCP connections to WhatsApp’s endpoints fail;

TCP connections to WhatsApp’s registration service fail;

DNS lookups resolve to IP addresses that are not allocated to WhatsApp;

HTTP requests to WhatsApp’s registration service do not send back a response to OONI’s servers.

TCP connections to web.whatsapp.com fail;

DNS lookups illustrate that a different IP address has been allocated to web.whatsapp.com;

HTTP requests to web.whatsapp.com do not send back a consistent response to OONI’s servers.

Facebook Messenger test

This test is designed to examine the reachability of Facebook Messenger within a tested network.

OONI’s Facebook Messenger test attempts to perform a TCP connection and DNS lookup to Facebook’s endpoints over the vantage point of the user. Based on this methodology, Facebook Messenger is likely blocked if one or both of the following apply:

-

TCP connections to Facebook’s endpoints fail;

-

DNS lookups to domains associated to Facebook do not resolve to IP addresses allocated to Facebook.

TCP connections to Facebook’s endpoints fail;

DNS lookups to domains associated to Facebook do not resolve to IP addresses allocated to Facebook.

Data analysis

OONI’s data pipeline processes all network measurements that it collects, including the following types of data:

Country code

OONI by default collects the code which corresponds to the country from which the user is running ooniprobe tests from, by automatically searching for it based on the user’s IP address through the MaxMind GeoIP database. The collection of country codes is an important part of OONI’s research, as it enables OONI to map out global network measurements and to identify where network interferences take place.

Autonomous System Number (ASN)

OONI by default collects the Autonomous System Number (ASN) which corresponds to the network that a user is running ooniprobe tests from. The collection of the ASN is useful to OONI’s research because it reveals the specific network provider (such as Vodafone) of a user. Such information can increase transparency in regards to which network providers are implementing censorship or other forms of network interference.

Date and time of measurements

OONI by default collects the time and date of when tests were run. This information helps OONI evaluate when network interferences occur and to compare them across time.

IP addresses and other information

OONI does not deliberately collect or store users’ IP addresses. In fact, OONI takes measures to remove users’ IP addresses from the collected measurements, to protect its users from potential risks.

However, OONI might unintentionally collect users’ IP addresses and other potentially personally-identifiable information, if such information is included in the HTTP headers or other metadata of measurements. This, for example, can occur if the tested websites include tracking technologies or custom content based on a user’s network location.

Network measurements

The types of network measurements that OONI collects depend on the types of tests that are run. Specifications about each OONI test can be viewed through its git repository, and details about what collected network measurements entail can be viewed through OONI Explorer or through OONI’s API.

OONI processes the above types of data with the aim of deriving meaning from the collected measurements and, specifically, in an attempt to answer the following types of questions:

-

Which types of OONI tests were run?

-

In which countries were those tests run?

-

In which networks were those tests run?

-

When were tests run?

-

What types of network interference occurred?

-

In which countries did network interference occur?

-

In which networks did network interference occur?

-

When did network interference occur?

-

How did network interference occur?

To answer such questions, OONI’s pipeline is designed to process data which is automatically sent to OONI’s measurement collector by default. The initial processing of network measurements enables the following:

-

Attributing measurements to a specific country.

-

Attributing measurements to a specific network within a country.

-

Distinguishing measurements based on the specific tests that were run for their collection.

-

Distinguishing between “normal” and “anomalous” measurements (the latter indicating that a form of network tampering is likely present).

-

Identifying the type of network interference based on a set of heuristics for DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking, and HTTP blocking.

-

Identifying block pages based on a set of heuristics for HTTP blocking.

-

Identifying the presence of “middleboxes” within tested networks.

However, false positives can emerge within the processed data due to a number of reasons. As explained previously (section on “OONI network measurements”), DNS resolvers (operated by Google or a local ISP) often provide users with IP addresses that are closest to them geographically. While this may appear to be a case of DNS tampering, it is actually done with the intention of providing users with faster access to websites. Similarly, false positives may emerge when tested websites serve different content depending on the country that the user is connecting from, or in the cases when websites return failures even though they are not tampered with.

Furthermore, measurements indicating HTTP or TCP/IP blocking might actually be due to temporary HTTP or TCP/IP failures, and may not conclusively be a sign of network interference. It is therefore important to test the same sets of websites across time and to cross-correlate data, prior to reaching a conclusion on whether websites are in fact being blocked.

Since block pages differ from country to country and sometimes even from network to network, it is quite challenging to accurately identify them. OONI uses a series of heuristics to try to guess if the page in question differs from the expected control, but these heuristics can often result in false positives. For this reason OONI only says that there is a confirmed instance of blocking when a block page is detected.

OONI’s methodology for detecting the presence of “middleboxes” - systems that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance and traffic manipulation - can also present false negatives, if ISPs are using highly sophisticated software that is specifically designed to not interfere with HTTP headers when it receives them, or to not trigger error messages when receiving invalid HTTP request lines. It remains unclear though if such software is being used. Moreover, it’s important to note that the presence of a middle box is not necessarily indicative of censorship or traffic manipulation, as such systems are often used in networks for caching purposes.

Upon collection of more network measurements, OONI continues to develop its data analysis heuristics, based on which it attempts to accurately identify censorship events.

Which types of OONI tests were run?

In which countries were those tests run?

In which networks were those tests run?

When were tests run?

What types of network interference occurred?

In which countries did network interference occur?

In which networks did network interference occur?

When did network interference occur?

How did network interference occur?

Attributing measurements to a specific country.

Attributing measurements to a specific network within a country.

Distinguishing measurements based on the specific tests that were run for their collection.

Distinguishing between “normal” and “anomalous” measurements (the latter indicating that a form of network tampering is likely present).

Identifying the type of network interference based on a set of heuristics for DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking, and HTTP blocking.

Identifying block pages based on a set of heuristics for HTTP blocking.

Identifying the presence of “middleboxes” within tested networks.

Findings

We confirm the blocking of 210 websites in Pakistan over the last three years, all of which are available here. Network measurements collected from 22 local networks show that ISPs blocked these sites by means of DNS tampering and by serving block pages through the use of HTTP transparent proxies.

Many block pages were only served for specific web pages hosted on HTTP, rather than for entire services (which could potentially lead to certain political and/or social cost). It’s worth noting though that we didn’t find any sites hosted on HTTPS to be blocked in the country throughout the testing period, and that many of the blocked URLs now support HTTPS.

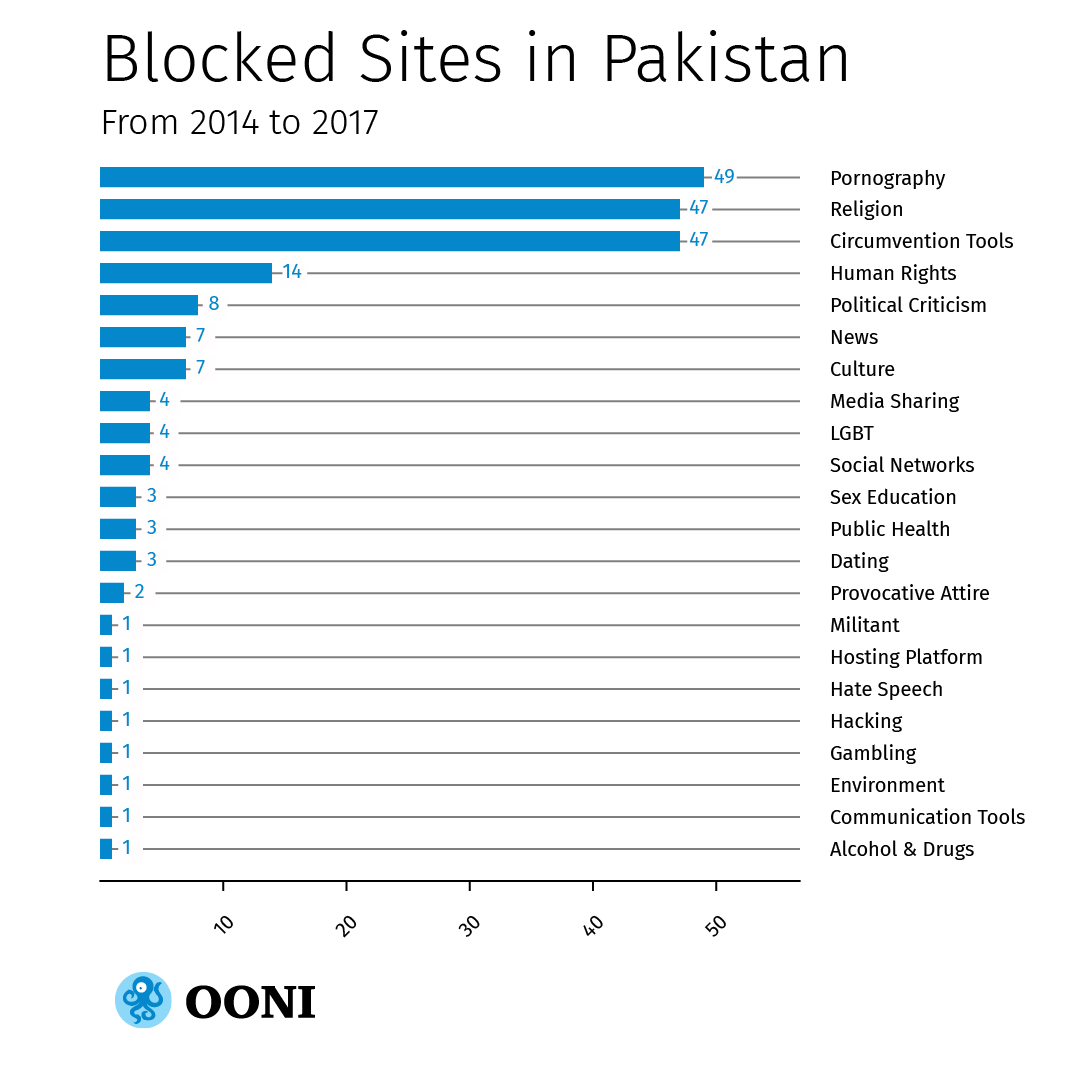

Censorship in Pakistan, according to OONI data, is mostly limited to pornography (which is illegal in Pakistan) and to sites hosting religious content considered blasphemous and political dissent. We also found a relatively large amount of circumvention tool sites (mainly web proxies) to be blocked, along with various other types of sites that fall under 22 different categories overall, as illustrated in the graph below.

These sites were not found to be blocked by all ISPs in Pakistan during the testing period, particularly since most network measurements were only collected from one network. A database detailing how and which URLs were blocked (and not blocked) across the 22 probed ISPs is available here.

Khabaristan Times, a Pakistani news satire publication that reports on national and local issues, was reportedly blockedin January 2017. As part of our testing, we collected one measurement indicating that this site was likely blocked by means of DNS tampering. This is also consistent with what locals in Pakistan reported to be experiencing when attempting to access khabaristantimes.com, which points to a message saying that the DNS address for the site could not be found. While we think it’s most likely the case that this site is blocked in Pakistan by means of DNS tampering, we cannot confirm this finding since only one measurement was collected during the testing period of this study.

Multiple middleboxes were detected across networks in Pakistan. However, it remains unclear whether these middleboxes are used for implementing internet censorship or for other networking purposes (such as cache-loading).

In general, most international sites and services were accessible, and OONI’s WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger testsconfirmed the accessibility of these apps during the testing period. Censorship circumvention tools, such as the Tor network, were mostly accessible.

These sites were not found to be blocked by all ISPs in Pakistan during the testing period, particularly since most network measurements were only collected from one network. A database detailing how and which URLs were blocked (and not blocked) across the 22 probed ISPs is available here.

Khabaristan Times, a Pakistani news satire publication that reports on national and local issues, was reportedly blockedin January 2017. As part of our testing, we collected one measurement indicating that this site was likely blocked by means of DNS tampering. This is also consistent with what locals in Pakistan reported to be experiencing when attempting to access khabaristantimes.com, which points to a message saying that the DNS address for the site could not be found. While we think it’s most likely the case that this site is blocked in Pakistan by means of DNS tampering, we cannot confirm this finding since only one measurement was collected during the testing period of this study.

Multiple middleboxes were detected across networks in Pakistan. However, it remains unclear whether these middleboxes are used for implementing internet censorship or for other networking purposes (such as cache-loading).

In general, most international sites and services were accessible, and OONI’s WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger testsconfirmed the accessibility of these apps during the testing period. Censorship circumvention tools, such as the Tor network, were mostly accessible.

Minority groups

The Baluchis are an ethnic minority in Pakistan and one of Asia’s cross-border minorities, divided between Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan. Since 1948, the Baluch nationalists have waged a guerilla war against the government of Pakistan, demanding political autonomy and greater control over Balochistan’s natural resources. Amnesty International reportedthat many Baluch activists, teachers, journalists, and lawyers have disappeared or been murdered in “kill and dump” operations by authorities, while attacks by Baluch armed groups have endangered civilians.

As part of this study, we found various Baluch sites to be blocked, as illustrated in the table below.

| Probed ASN | Blocked URL | Blockpage |

|---|---|---|

| AS23674 | http://www.BalochVoice.com | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.BalochVoice.com | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://balochwarna.org | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://balochwarna.org | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.bso-na.org | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.bso-na.org | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.ostomaan.org | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.ostomaan.org | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.radiobalochi.org | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://governmentofbalochistan.blogspot.com | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.BalochFront.com | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.balochunitedfront.org | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.balochwarna.com | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.balochwarna.com | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.thebalochhal.com | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.thebalochhal.com | id-surf-safe-0 |

The blocked URLs include the site of the Sweden-based Baluchistan People’s Party, which reports on human rights violations against the Baluchi. Other blocked URLs include Baluch news sites and independence sites, the blocking of which can probably be attributed to the sensitive political climate. The blocking of balochvoice.com, which currentlyserves as a resource for Search Engine Optimization (SEO) and online marketing, suggests that Pakistani ISPs might be blocking Baluch sites almost indiscriminately.

The Hazara ethnic minority in Pakistan has also experienced discrimination and abuse by authorities, as reported by Human Rights Watch. OONI data confirms the blocking of hazara.net, a non-profit which emerged in 1998 as a “direct response to the Hazara genocide in Afghanistan” and which reports on human rights abuse against the Hazara community.

It’s worth noting that none of the blocked Baluchi sites, nor hazara.net, support encrypted HTTPS connections. As a result, the blocking of these sites is enforced more than that of other blocked sites that support HTTPS (potentially enabling censorship circumvention).

A list of all other observed blocked sites in Pakistan is available here.

Religious criticism

Blasphemy is a serious crime in Pakistan. Penalties for blasphemy against Islam, under Pakistan’s Penal Code, can range from a fine to a death sentence. According to OONI testing, this prohibition is also enforced in the digital world.

Many of the URLs that we found to be blocked in Pakistan express criticism towards Islam, prophet Mohammad and other sacred personalities of religion Islam (and can be viewed as blasphemous), as illustrated in the table below.

| Probed ASN | Blocked URL | Blockpage |

|---|---|---|

| AS23674 | http://face-of-muhammed.blogspot.com | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.jihadwatch.org | id-micronet-0 |

| AS23674 | http://atheism.about.com/od/prophetmuhammadofislam/ig/Muhammad-Drawings-Pictures/ | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://dreamdogsart.typepad.com/art/2010/05/lars-vilks-muhammad-cartoon-dog-artist-attacked.html | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Everybody_Draw_Mohammed_Day | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Jyllands-Posten-pg3-article-in-Sept-30-2005-edition-of-KulturWeekend-entitled-Muhammeds-ansigt.png | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jyllands-Posten_Muhammad_cartoons_controversy | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lars_Vilks_Muhammad_drawings_controversy | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohammad | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/gabriel | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://europenews.dk/en/node/32286 | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://everybodydrawmohammedday.wordpress.com | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://face-of-muhammed.blogspot.com | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://friendlyatheist.com/2010/05/20/draw-muhammad-day-a-compilation/ | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://islam-watch.org | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://islamizationwatch.blogspot.com/2010/04/everybody-draw-mohammed-day-grows-in.html | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://twitter.com/MuhammadtheProp | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://twitter.com/ProphetMuhammad | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread564561/pg1 | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.bibleprobe.com/muhammad-cartoons.htm | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.buzzfeed.com/robertlangdon/the-prophet-muhammad-in-a-bear-suit-express-you | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.cagle.com/news/muhammad/ | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.drawmohammed.com | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.islam-watch.org | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.prophetofdoom.net | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.sodahead.com/united-states/seattle-cartoonist-launches-everybody-draw-mohammed-day-you-in/question-984209/ | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0T9UhBhTl9Q&feature=related | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Wu5e50zrPA&feature=fvst | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2L2ouAN770U&feature=related | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3sD-1-1sbik | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=43LMQXYhyt0&feature=related | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AMRaxkgCUfI&feature=related | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KlYLKf4q2rg | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LyKdYTzMqWo&feature=related | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OMz0aIM2_sM | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XJMlgmwHN9E | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zsv1SToU1xo&feature=related | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4yfG5dAZdU | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKJtedW9KN4&feature=related | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nycuLpw0VV8&feature=related | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDrti5T93T8 | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5rPSTLy394&NR=1 | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5rPSTLy394&feature=related?http://www.xroxy.com/ | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7ok4njJXI8 | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.zimbio.com/War+on+Terrorism/articles/6NAIGjWobep/WASHINGTON+POST+Seattle+cartoonist+Molly+Norris | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | http://www.zombietime.com/mohammed_image_archive/ | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS23674 | https://barenakedislam.wordpress.com/2010/05/02/muslim-hackers-get-their-filthy-finger-licken-hands-on-kfc-website/ | id-surf-safe-0 |

| AS24499 | http://www.prophetofdoom.net | id-surf-safe-0 |

Most of the blocked URLs host content pertaining to “Everybody Draw Mohammed Day”, a controversial and viral online campaign that encouraged artists around the world to draw representations of the Islamic prophet Mohammed. U.S. cartoonist Molly Norris started the campaign in 2010 in response to online death threats made against the creators of the “South Park” show, which attempted to satirize the Islamic prophet Mohammed.